Happy Birthday, Evelyn Underhill

Some thoughts on the 150th birthday of a great English mystical writer

December 6 is the Feast of Saint Nicholas, patron saint of children, and the template for Santa Claus.

It’s also the birthday of many amazing and talented people, including the Welsh spiritual writer Dion Fortune (born on this day in 1890), Jazz musician Dave Brubeck (1920), Polish composer Henryk Górecki (1933), Japanese composer Joe Hisaishi (1950), Peter Buck, guitarist for R.E.M. (1956), Nick Park, creator of “Wallace and Gromit” (1958), and Hollywood Director Judd Apatow (1967).

It’s also my birthday. So, no wonder I’m a bit interested in this day!

But what I think really makes December 6 special, especially for those of us who love mystical and contemplative spirituality, is that it is the birthday of arguably the most important English writer on mysticism in the twentieth century: Evelyn Underhill.

Born in Wolverhampton, England in 1875 (she died in London in June of 1941), Underhill was the daughter of a British barrister and grew up in a home that was only nominally Christian. From an early age, she was drawn to spiritual matters, and, traveling many times in her youth with her mother to Europe, she grew to love the heritage of Christian art and architecture, from which blossomed her interest in the great mystics — not only of Christianity, but of the world. Self-taught, she studied the writings of the mystics at a time when women rarely were invited to pursue higher education and certainly had no access to ordained ministry. After years of exploring the mystics on her own, at the age of 35, she published an extraordinary book, Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Spiritual Consciousness. Some have speculated that she was able to find a publisher — and an enthusiastic reception for the book among the public — only because in her day, Evelyn was more typically a man’s name than a woman’s (think of the novelist Evelyn Waugh). Hey, whatever it takes.

The success of Mysticism led to a vibrant and prolific writing career over the last thirty years of her life, paired with a deepening of her own spirituality through a spiritual director, the Austrian Catholic writer Friedrich von Hügel, who interacted with her from the time the book was published in 1911 to his death in 1925. His style of “spiritual direction” was patriarchal and authoritarian, but at that time this kind of hierarchical guidance was the norm. Nevertheless, he encouraged Underhill to be engaged more seriously with the Christian tradition, to make participation in a faith community and care for those in need essential to her spirituality, and to take more seriously the role that Christ plays in Christian mysticism. By the time of von Hügel’s death, Underhill was already beginning to write more about spirituality and less about mysticism — a transition that made her work not only more palatable to the church community, but also more humble, down to earth, and accessible. Nevertheless, the depth and interior insight that marked her more mystical writings continued to inform her later, more spiritually-centered writings as well.

She was a trailblazer: the first woman to lecture on religion at Oxford University, while strictly as a guest presenter — still, a significant achievement. In her later years she became a noted retreat director, and led retreats at several locations throughout England, although none was as close to her heart as the Chelmsford Diocesan Retreat House in the village of Pleshey, about 50 miles of northeast of London — a spiritual center she described as “soaked in love and prayer.” The Pleshey Retreat House is still operating today, and often hosts retreats and conferences based on the wisdom of Evelyn Underhill.

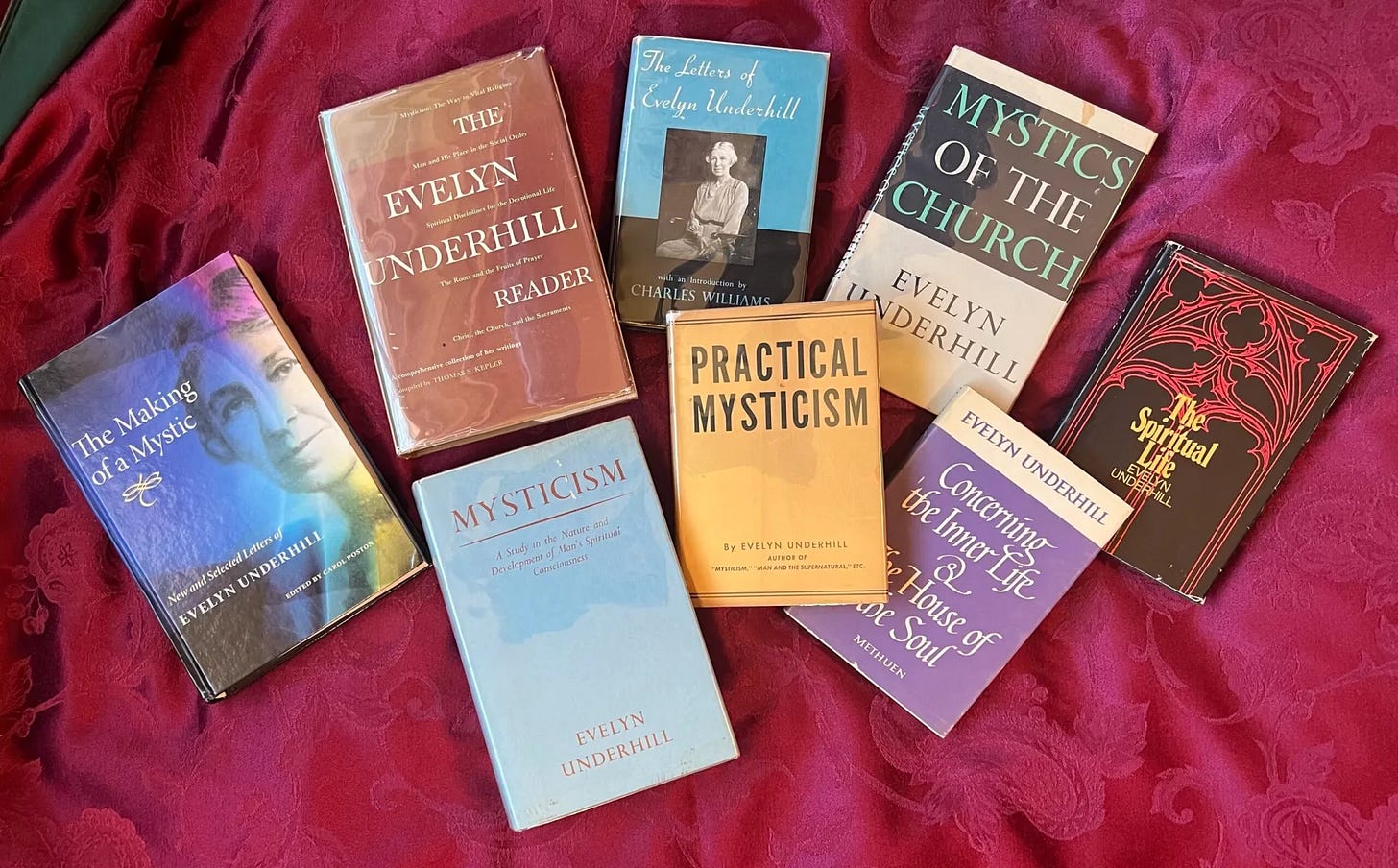

I have often told the story of how I became a fan of the wisdom of this unassuming British laywoman. After an intense dream I had about the end of the world the summer after I graduated from High School, an older friend gave me a copy of Mysticism, remarking that he thought I would enjoy it (I later learned he was in the habit of giving multiple copies of that book away!). I did indeed enjoy it, for it introduced me to the main ideas, major figures and spiritual principles that give mystical and contemplative spirituality its distinctive character. Thus began a lifelong love for Underhill. Other books of hers that I have found meaningful or helpful include The Spiritual Life, The Golden Sequence, The Mystics of the Church, as well as anthologies of her work such as The Evelyn Underhill Reader and An Anthology of the Love of God. But the two books that, after Mysticism, have made the greatest impact on me were The Letters of Evelyn Underhill (revealing the warm, friendly, “behind the scenes” side to her personality) and what I now consider her masterpiece, Practical Mysticism. Now more than a century old, it does show its age a bit, but it remains a beautiful introductory invitation into a life shaped by contemplative prayer — and was certainly ahead of its time, published decades before similar books were released by writers like Thomas Merton, Richard Rohr, and Thomas Keating.

So, what does Underhill have to say to us about mysticism? As the title of that book implies, she saw mysticism as a practical type of spirituality, not some airy or dreamy foray into what nowadays people might pejoratively dismiss as “woo-woo.” She never tried to minimize the awe and wonder that mystical spirituality can evoke in our hearts, but she always preferred a mysticism grounded in ordinary practices such as prayer, meditation, service to those in need, and seeking to conform life to the beautiful demands of love. For her, God is more than just an abstract concept or an abstract force: like all the great mystics throughout history, she experienced and wrote about God as a real presence in our hearts and our lives, a personality shaped by and flowing with love, who calls us to calibrate our lives to both the splendor and the sacrifice that authentic love entails. So, for Underhill, mysticism is never just an amusing pastime or spiritual hobby — it is a thorough and transforming way of life, that anyone who accepts its call can expect to be forever shaped and reshaped by the profound and wonderful nature of love.

There’s so much more to say about Underhill, but perhaps the best way for me to celebrate her birthday (and invite you to do the same) is by sharing with you an excerpt from my book The New Big Book of Christian Mysticism, which was explicitly written as a kind of homage to her legacy. This excerpt looks at how Underhill defines the nature of contemplative prayer in Practical Mysticism. It shows how, more than 80 years after her passing, Underhill’s mystical wisdom remains as relevant — and important — as ever.

THREE FORMS OF CONTEMPLATION

In Practical Mysticism, Evelyn Underhill articulates a threefold way of understanding contemplative prayer. Her model is quite useful and well worth summarizing here.

Discernment. The first form of contemplation invites us to recognize how God can be found in all things. This is a recurring theme in the writings of the mystics, and the theological term for God’s presence in creation is immanence (which is paired with transcendence, the principle that God cannot be contained by any created thing, not even by the universe as a whole). Discernment, in the sense Underhill uses the term, refers to our capacity for awareness of the immanent presence of God in and through nature—including the nature within us, which is to say our own hearts. Contemplative discernment means learning to sense the presence of the artist by gazing upon and appreciating the beauty and wonder of the artwork.

Recognition. The artistry of creation introduces us to the Spirit who dwells in us and in all things, but it can never capture the fullness of that divine presence—an immanence that is also paradoxically transcendent. Knowing that the God who is not elsewhere also transcends all created things, we are invited to enter the “cloud of unknowing” where we seek God, not in any created object, but in silence and darkness, in the mysteries of our own being and consciousness, knowing that even the human soul, vast as it is, can never fully embrace and reveal the limitless splendor of our divine lover.

Acknowledgment. As we discern God’s presence in all things, and recognize God’s mysterious unknowability, we are moved to accept the limits of even our own consciousness and spirit; we humbly acknowledge that no created thing, not even the diamond-fashioned interior castle, can ever fully reveal God to us, and so we consent to wait in the silence and darkness, trusting that, even beyond all human experience, God can, will, and does come to us without any effort on our part. This marks the transition from “active” to “infused” contemplation—in other words, the transition from contemplation as our intentional practice, moving instead to the humble acknowledgment that contemplation is God’s practice, which we receive as a free gift of grace. Acknowledgment transforms our prayer from an exercise in seeking spiritual fulfilment to a fully God-centered act of loving response to the infinite, ultimate, ineffable mystery.

While Underhill’s three forms of contemplation are certainly not the only way, or even perhaps the best way, of understanding the process by which we enter into the wordless wonder of silent adoration, they do illustrate that contemplative prayer is not something anyone can master; it is not some technique to work at until you get it right. Contemplation is a lifelong (and beyond) process of ever-unfolding possibilities that move us deeper and deeper into encounter and intimacy with God—an encounter that occurs beyond the limits of all our thoughts, ideas, mental images, and ability to know the ways of the Spirit.

To climb halfway up the mountain is not to reach the summit, even though the view from that mid-point of your journey may be spectacular. The mystical life calls us to the summit. When we embrace a spirituality that calls us into silence and beckons us to let go of the comforting but constraining cocoon of spiritual ideas and religious thoughts, ultimately, we are being called into a process that will never end—not even in the silence of eternity. We will have no choice but to see this journey through to the very heart of the mystery—not only here and now, but everywhere and forever. (New Big Book of Christian Mysticism, p. 291-293).

PRACTICING THE PRAYER OF RECOLLECTION

The Prayer of Recollection is a traditional form of Christian prayer, which Evelyn Underhill describes as “the disciplining and simplifying of the attention.”

The heart of the prayer of recollection is simply placing your attention on a single point that represents God and your intention to be present to God alone. This single point could be a word, an image like an icon, or even your breath. Underhill describes the prayer of recollection as “dwelling” on your point of attention, rather than thinking about it — “as one may gaze upon a picture that one loves.” She suggests that by dwelling on, and indeed in, this point of spiritual attention, that we may fall into a state of reverie, which she describes as a “holy daydream.”

The prayer of recollection invites us to simply rest in the presence of God, even if we don’t consciously feel or experience that presence. We know as an article of faith that the Holy Spirit has been poured into our hearts. Recollection, which simply means prayerfully placing your attention on that simple point of awareness, allows us to rest in that Divine Presence, without having to think elevated thoughts or come up with the right words to say.

But what if your mind wanders? We all have distracted minds — and hearts. So, it’s normal for your attention to flit from this to that. The prayer of recollection is about placing your attention on God, and then when it wanders off, simply returning it to God. No judgment, no force. Simply allow yourself to rest in attention to God and return to that attention whenever you need to. Remember, the real prayer is happening in your heart. So gently call your attention to God as often as you need to, while allowing your heart to rest in God’s love. This is the heart of recollection.

***

If this sounds to you a lot like more recent contemplative practices that have become popular like Centering Prayer or Christian Meditation, that’s because Underhill (inspired primarily by Teresa of Ávila and John of the Cross) is standing in the same mystical tradition as those later spiritual practices. I’m sharing this with you today to celebrate Underhill’s undying contribution to the mystical life — but also an invitation. If the above practice appeals to you, try it out. It might just be the doorway into contemplation that speaks especially to you.

Happy 150th Birthday, Evelyn Underhill! And thank you for your contribution to the study and practice of mystical spirituality in our time.

If you love mystics like Evelyn Underhill and Julian of Norwich, join me on a pilgrimage in search of the “Wisdom of the English Mystics” in England, May 27-June 2, 2026. Our journey will include two nights at Underhill’s beloved Pleshey. For information or to sign up, click here.

Quotation source:

McColman, Carl. The New Big Book of Christian Mysticism: An Essential Guide to Contemplative Spirituality (Kindle Edition), p. 291-293.