The Decline of Christianity... and the Future of Mysticism

"The Christian of the future will be a mystic" — but what will the mystic of the future be?

Yesterday I was chatting with a friend who, like me, grew up in a conservative Christian environment and mostly internalized a religious approach to spirituality, but then (again, like me) has grown to embrace a much more expansive spirituality as an adult, exploring indigenous, earth-centered, mythopoetic and other approaches to the mystical life.

During our conversation, I mentioned that my perception of him was that he had pretty much disengaged from your garden-variety, Sunday-go-to-meeting type of church involvement. I asked him if that was accurate.

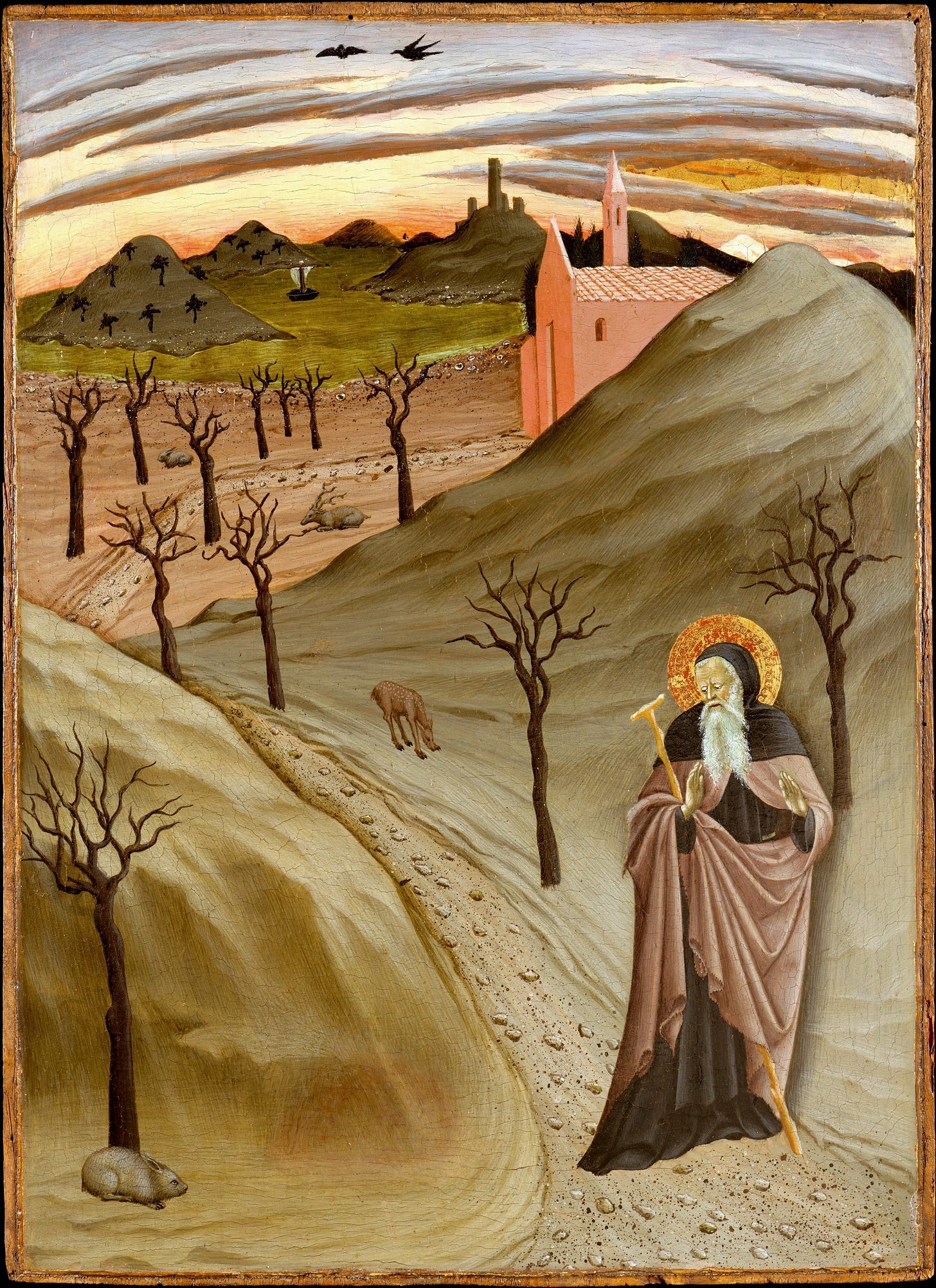

“Not exactly,” he said, clearly pondering my observation. Then he expanded on it: “maybe I have disengaged, but in the sense that the desert fathers and mothers were disengaged from the institutional church of their day.”

What a wonderful insight, and now it was my turn to ponder what he had just said. My friend was not directly comparing himself to a desert father: after all, he’s an ordinary middle-aged guy with a successful career and a beautiful family. His point was not that he is about to run off into the wilderness to become a hermit — but rather to note that there are many reasons why someone’s relationship to faith community (like church) can change over time.

The Fashionable Abandonment

It is fashionable in our time to give up on religious observance.

Churches, frankly, have terrible reputations, at least in society at large (people who remain actively involved in Sunday-morning religion seem to be the last to get the memo). Between Christian nationalism, opposition to feminism and the queer community, subtle messaging that “our way is the only way” (or the liberal version, “our way is the best way”), and just a general sense that religious observance is either ideologically conservative-to-reactionary or just plain dowdy and old-fashioned, it seems that religion has increasingly become unpopular — except among those who remain religious/cultural conservatives, or a very small percentage of social-justice liberals. As for contemplatives (and mystics)? Apparently, too few to even be statistically significant.

More and more people seem to be giving religion a hard pass — and the younger a person is, the more likely they are to say “Thanks, but no thanks.”

Even in my youth, I was familiar with the concept of “spiritual but not religious” (SBNR), as a handy moniker for those who disengage with religion but not with their own inner development. Even thirty years ago, when I was writing my first book, I was reckoning with the rise of this perspective, especially among young persons (the fact that many Christians get all judgy about this — think of Lillian Daniel’s famous 2011 essay calling SBNR folks “boring” — has not helped the Christian cause). Other terms for the spiritually-engaged but religiously-disengaged include “Spiritually independent,” “Nones” (as in “Religious Preference? None”) and, based on an idea made popular by Aldous Huxley, “Perennialists.”

Over the years I’ve watched as different events in our shared common life have continued to chip away at church as we’ve known it. The events of 9/11 cast a bright light on the ugliness of religious extremism, which seemed to amplify the exodus from religious practice, even from mainstream religion. For a time, there were still signs of hope, like the resurgence of progressive Christianity in the 1990s and early 2000s, known as the “emergent church” — but with the rise of neo-conservative political movements like the Tea Party and then MAGA, it seemed that the Christian left became eclipsed by the more ominous upswelling of hyper-conservative religion, marked by a backlash against feminism and the queer community, ultimately emerging as Christian nationalism. Then with the COVID pandemic, many churches pivoted to online worship, disrupting the mainstay of religious life, Sunday morning worship — and then when the lockdown passed and vaccinations made it safer to return to public gatherings, too many churches found that their membership just continued to dwindle further and further.

The Survival of Mysticism After Religion

Which brings me back to my “disengaged” friend. As I mentioned, he is hardly someone who has traded in his religious practice for a kind of shallow secularism. In fact, I know few people who are as dedicated to nurturing their inner life as him. Perhaps it’s not surprising that he would make sense of his own spiritual independence by appealing to the memory of an entire community of mystics and contemplatives who abandoned the common religious observance of their time to seek God in radical solitude, far away from the creature comforts of civilization.

This is not to suggest that we must all retreat into the forest or the desert in order to grow spiritually, even though that’s precisely what our spiritual ancestors in places as far-flung as Egypt and Ireland chose to do.

Nor is it required that we join monasteries (even though the desert mothers and fathers were pretty much the first Christian monks and nuns). Rather, I think if we can see the desert hermits as inspiring ancestors of today’s spiritually independent persons, the lesson is really more along these lines:

The heart of spirituality is mysticism. And mystics have always lived and functioned on the margins — the margins of society, the margins of religion, and even the margins of the monasteries. When Karl Rahner said “the Christian of the future will be a mystic,” perhaps he was implying this: the future of spirituality is mystical — whether or not we choose to be connected to institutional religion.

So the Christian of the future will be a mystic, or will simply not exist, according to Karl Rahner. And I largely agree with him, even though are plenty of non-mystical and even anti-mystical Christians running around, but it seems to me that many of these folks are either Chinos — Christian in name only (for example, Christian nationalists) — or simply well-meaning folks who grew up with cultural Christianity and haven’t found it in their heart to give it up yet. But if they don’t, their children or grandchildren will.

The Christian of the future will be a mystic. But what will the mystic of the future be?

Envisioning the Mystic of the Future

For years, I thought that mysticism needed some sort of communal and institutional grounding in order to thrive. In other words, individualistic mysticism is a recipe for ego inflation, spiritual narcissism, experiential solipsism, that sort of thing. But I’m increasingly persuaded that while healthy mysticism does require community, institutional forms of community are, frankly, optional at best.

Future-Christians need to be mystics, because non-mystical Christianity tends to go off the rails (exhibit A: Christian nationalism; exhibit B: watered-down liberal Protestantism). But future-mystics do not need to be Christians, even if their mysticism is grounded in the New Testament and the teachings of the Christian mystics.

There, I said it. I’ve been thinking this for a while now. It’s good to get it off my chest.

There will always be some mystics who have a gift for navigating the challenges of institutional religion, so there will always be some contemplative and mystically-minded folks who continue to participate in Sunday-morning religion. This will be true whether such persons are clergy (ordained ministers) or laypersons. And let me say this once again because it’s important: I hope that anyone who is serious about following the wisdom of the mystics will make community a priority, even if they cannot thrive in institutional communities.

I guess what I’m saying is that the church needs mystics more than mystics need the church. Howard Thurman pointed this out back in 1939, during a significant talk on “Mysticism and Social Change” that he delivered at Eden Seminary in St. Louis:

When [acts of worship] become institutionalized they are apt to become dead so the mystic seems always to be the foe of institutional religion. He is very sensitive to the crystallizing of acts of worship into dead forms. It is profoundly true that he does not stand in need of the institution or the institutional forms as such. Even in Catholicism any careful reading of the testimony of the mystics convinces one that the church has no real friend in the mystic.

“The church has no real friend in the mystic” — it took me a long time to accept that this is true, and I think I had to first recognize its inverse: that mystics have no real friend in the church. Officious churchmen and self-appointed enforcers of orthodoxy have been accusing mystics of heresy, pantheism, new-ageism, syncretism, disobedience, rebelliousness, and other boogeymen charges not just in our time, but (using different slurs, like “quietism” or “illuminism” or “presumptuousness”) over the centuries.

Far be it from me to suggest that mystics and contemplatives can never make mistakes: we’re all human, after all, including those of us who encounter God through silence, mystery, and experience. So everyone can get lost in the woods sometimes. But is an institution necessary to keep us on the straight and narrow? How could it be, given how prone the institution is to its own errors and distortions?

The fact that mystics like Meister Eckhart, Teresa of Ávila, John of the Cross, Thomas Merton, Teilhard de Chardin, among many others, have managed to remain engaged with institutional Christianity even while they have been attacked (and in Marguerite Porete’s case, killed) speaks, to me, of their generous spirits as well as their patience and capacity for long-suffering.

But we need to avoid the assumption that the choice these historic mystics made must necessarily be the “right” choice for us today. As my friend who compared himself to the desert elders reminds us, there is a tradition of mystics who have conscientiously disengaged from the institution precisely in order to deepen their own contemplative practice.

Many of us may discern that we are called to do the same today — not necessarily by withdrawing into the wilderness or becoming monks, but instead by exploring interspirituality, or prioritizing the struggle for justice, or even just taking refuge in marginal communities that are at least less institutionalized, like the Quakers or the Unitarian Universalists or the various house churches and independent sacramental communities. There are many ways to find community, and many of these avoid the problems of religious institutionalism.

When I worked for the Trappist monks, I met quite a few people who were sincere in their love for Catholic spirituality, loved to visit the Abbey, often making retreats or attending monastic liturgy — but who never darkened the door of their local Catholic parish. Not all of those people thought of themselves as mystics or contemplatives — but I’m sure some did, and others may have been the type of “masked contemplatives” (a term coined by Jacques Maritain and later used by Thomas Merton) whose deep mystical spirituality was marked by humility, simplicity, lack of fuss, and lack of concern with labels — but real and truly mystical nevertheless.

Again, this is the mystic of the future. And the Christian of the future may very much need to be this kind of person.

The Meaning of Future-Mysticism

What, then, does all this mean?

If you are the type of person who still values Sunday morning religion, by all means be true to what you love: but try not to get discouraged every time another church closes its doors. Remember that the Spirit who leads us to love, mercy, forgiveness, empathy, enlightenment, illumination and even theosis does not need a building — or an institution — to continue working in human hearts.

And if you are not inclined to be religious (or engaged with institutional Christianity or any other institutional faith), consider how you can continue to embody, and form within yourself, the best and most challenging teachings of Christ and the mystics: be merciful, be forgiving, be communally-minded, be radically loving, be nonjudgmental, love your enemies, pray without ceasing, meditate joyfully, contemplate humbly, and cherish the mystery in your mind, heart, gut and body. And look for how that mystery inspires you to love, serve, and cherish others. Do this, and you will — I believe — be on the road to mystical enlightenment and contemplative joy.

And by doing so, you will be a living embodiment of divine love. And that, it seems to me, is what mysticism, or contemplative practice, or even spirituality and religion at its best, is meant to be.

Quotation source: A Strange Freedom: The Best of Howard Thurman on Religious Experience and Public Life (p. 115).

Was it Andre Gide who said the future of Christianity will be mystical, or it will not be at all?

In any case, this question of "spiritual but not religious" has always fascinated me. When people argue in favor of institutional religion, they always seem to assume the choice of what religion is obvious.

Am I Christian because I grew up in the United States? (this gets to the recent Charlie Kirk inspired question of what it means to claim the US is a "Christian" nation, but we'll let that one go at that for now)

Let's see. When I was born, in the early 1950s, my parents had already joined the Unitarian church - which I later found out was not due to any religious interest on their part but "for the sake of the children." I begged them to let me stop going when I was 11; not for any grand reason but because I found it so deadly boring (I've tried again since, by the way - two services over the course of 30 years in NY City; one in Greenville, SC, one in Asheville, NC and one in Black Mountain, NC - astonishingly, just as boring as the ones back in the 1950s!!)

I had no idea - really - I had a Jewish background until one day in the car, one of the last Sundays I went to Unitarian church, my mother casually mentioned something about a rabbi in our ancestry. having already absorbed the general atmosphere of anti semitism in my relatively conservative New Jersey suburb, I was horrified that I was "one of them" (it took a few years to get over, but now I have a good deal of pride in my Jewish roots)

I'll quickly pass over the fact that I became a "mystic" one day when I was 17 (May 1970) but wondered for maybe 20 years if I was meant to be part of some institution. I thought of becoming a Tibetan Buddhist monk and living in Dharmsala; that was 1974, but the next year I met a teacher in the tradition of Sri Aurobindo, and I've been in that tradition now for 50 years. It's hard to imagine any group more anti institutional than the Sri Aurobindo folks - "No rules!" is one of our favorite quotes from MIrra Alfassa (the Mother)

But back to Christianity. I did hear people saying one must get in touch with one's own cultural roots. So, I fell in love with Brother Lawrence's Practice of the Present of God when I was 20, and the same year loved "The Way of the Pilgrim." I also read the Bible - cover to cover - twice that year (though, confession time, I did actually skim through Leviticus and Numbers)

I was the music director of a Spanish Catholic church throughout the 1980s, and the fact that I kind of understand Spanish when I pay attention meant I could zone out just a bit and enjoy the music of the mass without having to be annoyed by the sermons (Father Alphege, a gay - but non abusive - alcoholic priest, happened to be a deeply contemplative man, and over the years he taught me a great deal about Christian contemplative practice, always recommending the Cloud of Unknowing and sharing his Marian devotion).

But I honestly could never understand what the appeal of conventional religion was. It felt like at best an appeal to conventional ethics and in its minimal form (this is apart from the utter horror of fundamentalist religions) seemed to be a social gathering place). How people could hear things like "Not I but Christ in me" or "In you is the Light of the world" or God is "he in whom we live and move and have our being" and not desperately yearn to live 24 hours a day in his/Her Presence; I could never understand how religious people so completely miss all that!

Anyway, I didn't have Carl McColman's books to guide me back in those days; perhaps that might have helped!!!