The Arrows of Desire

How Ordinary Human Yearning is a Doorway to the Mystical Life

Is desire the enemy of the spiritual life?

The Buddha’s four noble truths could leave you with the impression that he viewed desire as the root cause of suffering. Taṇhā, from the Pali word for “thirst, longing, greed, or desire,” is viewed as the cause of suffering — therefore to find relief from suffering, we need to extinguish our taṇhā or desire. In a similar way, the New Testament letter attributed to James offers a pretty grim understanding of how dangerous desire can be: “One is tempted by one’s own desire, being lured and enticed by it; then, when that desire has conceived, it gives birth to sin, and that sin, when it is fully grown, gives birth to death. (James 1:14-15). Yikes!

Ideas like these can lead to the conclusion that it is bad even to have normal desires — the desire for food, for shelter, for comfort, for physical and emotional intimacy. It’s a short jump from this to the assumption that sexual expression and even romantic intimacy is somehow a kind of betrayal of the spiritual life. This way of thinking shows up again and again in the history of Christian spirituality, from the discomfort with “fornication” found in the sayings of the desert mothers and fathers down to the grim austerity of the Puritans and the carefully regulated Purity Culture found in at least some corners of today’s evangelical world (and which is primarily geared toward controlling girls’ and women’s bodies).

It’s interesting how the language from James 1:14 explicitly describes desire using erotic imagery, speaking of desire “conceiving” and “giving birth” to sin. I suppose this is not too surprising, since sexual desire can certainly be overwelming in its power and insistency. Is it any wonder that a spirituality based on transcending desire would end up advocating for the repression of sexual yearning? We see this on full display among the desert fathers, some of whom were, monks so beset by lustful thoughts of beautiful naked women dancing around them, leading them to conclude that their sexual desire was nothing other than an impediment to their commitment to a sober life of prayer.

But right away, we can see the contradiction at the heart of the “desire is bad” mentality: for the problem with sexual longing is not that it represents how all desire is considered wrong, but rather that erotic yearning competes with an entirely different type of desire: the desire to be spiritually pure, sinless, and/or to give oneself entirely to God.

Even the desire to have no desire is itself a desire. So when any religious or spiritual teacher dares to say desire is bad or desire is the problem, they are indulging in what Ken Wilber calls a “performative contradiction” — a philosophical fallacy that inherently results in logical problems. To say “desire is the enemy of spirituality” is a performative contradiction because it is an expression of its own unique form of desire: the desire to be free of desire.

If desire in itself is not the problem of the spiritual life, then how can we free ourselves from the long heritage of rejecting desire in the mystical tradition? In other words, how can we cultivate a spiritually healthy relationship with desire? What would that look like and how can we make it manifest in our lives?

Perhaps we need to begin by changing the way we perceive and understand desire. It seems to me that the “desire is bad” viewpoint is based on a kind of binary approach to embodiment, where desire and lack-of-desire are seen as zero-sum alternatives. But that’s not really how desire works in human experience, is it? Most ordinary human desires seek goods or experiences that can help us to live and to love well. We need food and drink to survive. We need intimacy and sexuality to find joy in life and to propagate the species. Many of these desires can be fulfilled through the ordinary tasks of living, and when a desire is fulfilled, it ceases, at least for a time. But ordinary human desires are part of a cyclical experience of desire, fulfillment, satiation, and then eventual return of the desire. When our hunger and thirst is satisfied by food and drink, it is only a matter of time before we hunger and thirst again. We satisfy our desire for sleep by resting, but tomorrow we will eventually be fatigued again. So desire and the fulfillment of desire is a cyclical reality — like suffering and the end of suffering, a dynamic the Buddha spoke of in his teachings.

We embody many desires: for food and drink, of course, but also for many intangible goods: for a life and career that is fulfilling, for the satisfaction of being creative or making a difference in life, and even for some sense of spiritual meaning and purpose, a sense of connection with the Spirit. This rhythm of desire and fulfillment can actually be a profound blessing — for isn’t a glass of water more refreshing and satisfying when our thirst has become acute?

In other words, it seems that desire can not only create suffering, but it can also open us up to experience a profound sense of satisfaction, since desire impels us to seek fulfillment, which in turn gives us that sense of relief or gratification.

We see this play out spiritually as well. In the second of her sixteen showings, Julian of Norwich speaks of “seeking” and “seeing” God. It is clear that the seeking is a type of desire. Julian acknowledges that we would rather have an experience of God in prayer (what she calls “seeing” or “beholding” prayer) than to have a more empty kind of prayer in which we seek, but do not consciously experience, the God to whom we pray. But then she says something surprising: that God is more pleased with our seeking (desiring) God than with those times when we seem to have a satisfying experience of seeing/beholding God. In other words: desiring God in prayer is, paradoxically, a way of praising and blessing God.

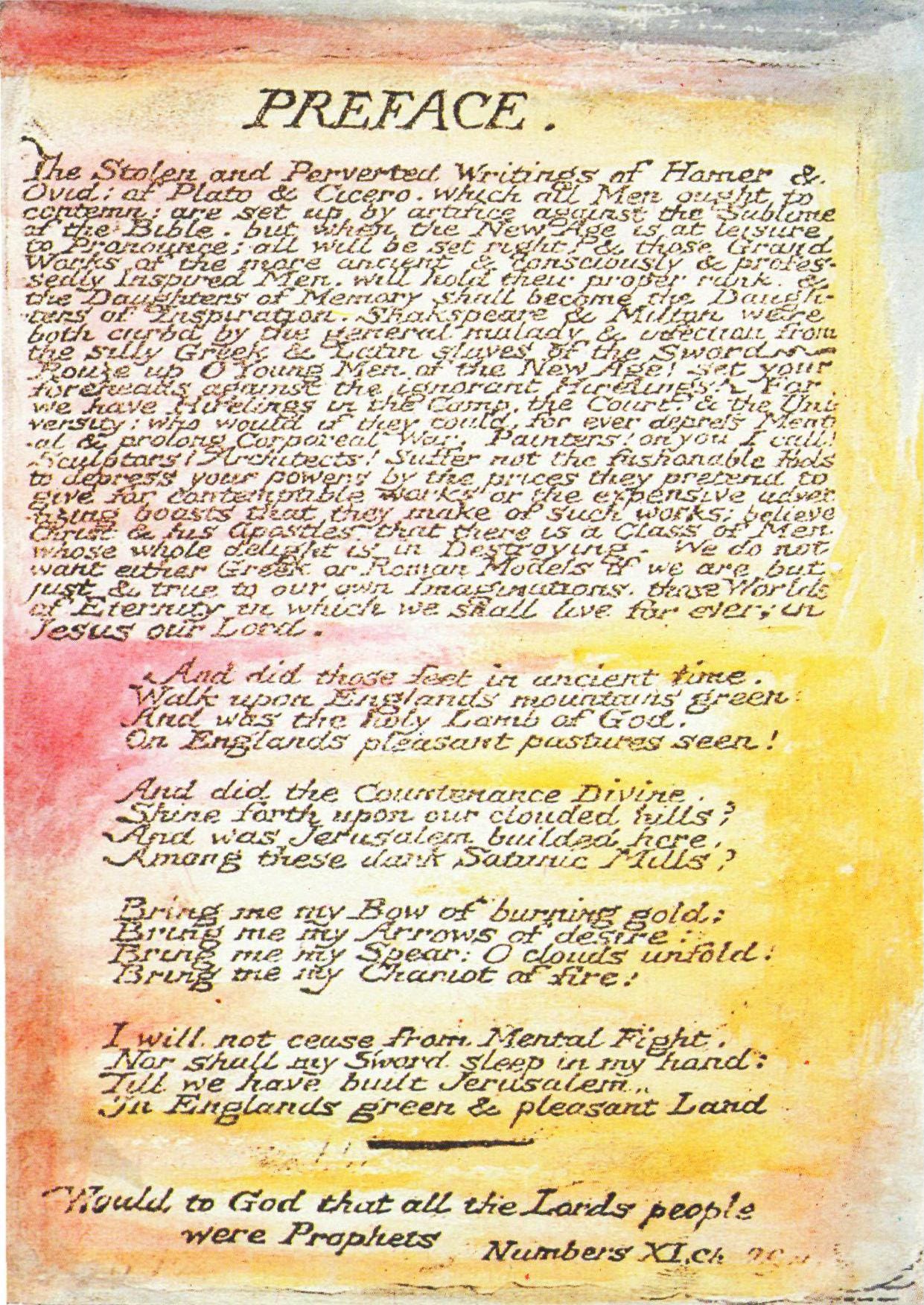

In his poem “Jerusalem,” William Blake writes:

Bring me my Bow of burning gold:

Bring me my arrows of desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold!

Bring me my Chariot of fire!

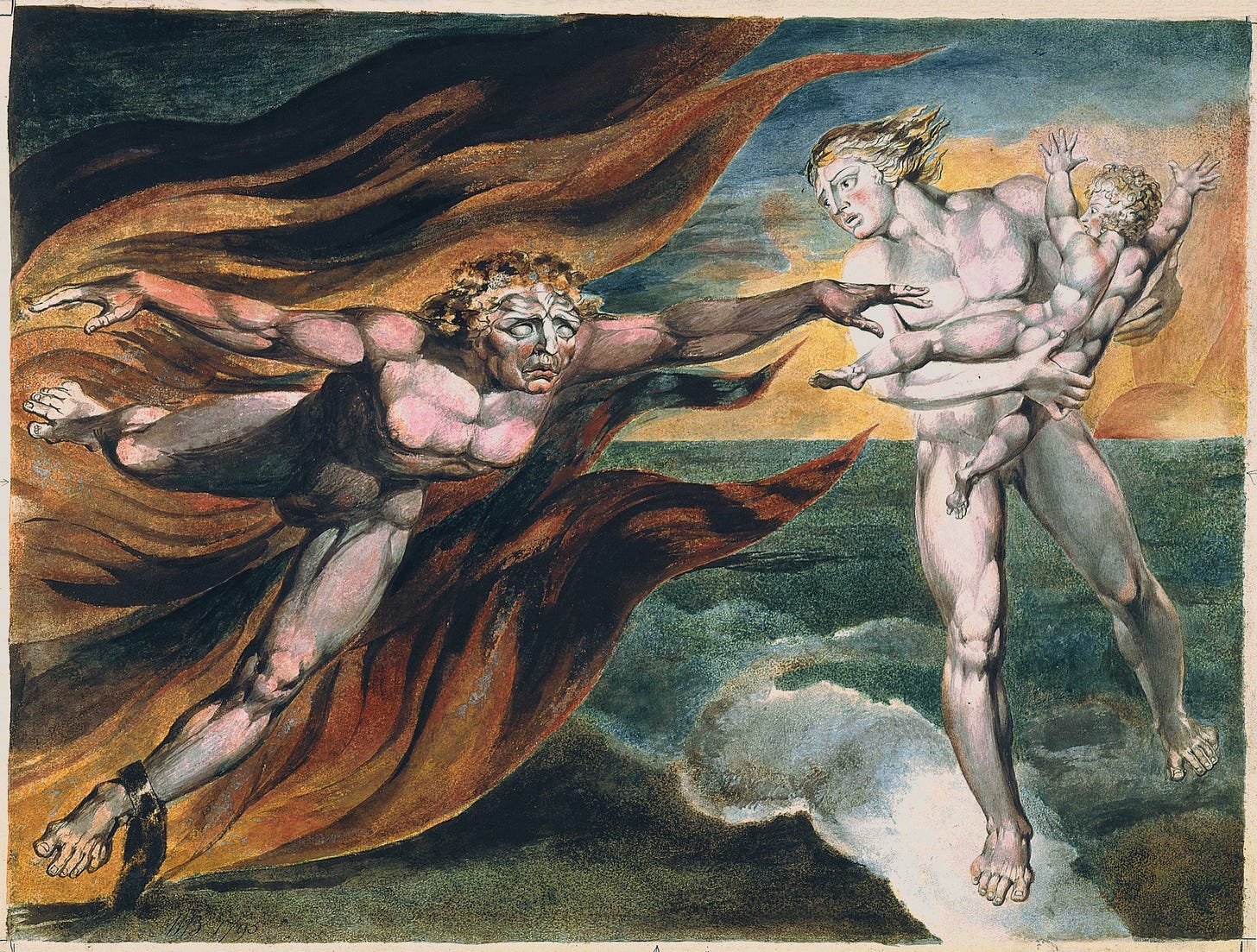

What are these arrows of desire? This poem invites us to reflect on the idea that Jesus may have walked on “England’s mountains green” — an allusion to the legend that Joseph of Arimathea was a traveling merchant who came to Cornwall to trade in tin, and may have brought Jesus with him, when Jesus was just a boy. But Blake’s poem is not merely an expression of pride in some imagined past: it is an expression of hope for a future when the new Jerusalem does not merely descend from heaven (as described in the Bible’s book of Revelation) but is actually built in “England’s green and pleasant land” — and so the bow, the arrows, the spear and the chariot represent the symbols of struggle, as the narrator of the poem commits to the “Mental Fight” of struggling to make this new Jerusalem manifest.

For Blake, desire is somehow linked to hope, to what theologians call an eschatological hope — a hope that things will someday be made right, even if that someday only comes at the very end of time.

In Psalm 37, verse 4 — one of the single most beautiful verses in the entire Bible — we read this deeply contemplative invitation:

Take delight in the Lord,

And God will give you the desires of your heart.

This seems to be a long way indeed from the dour notion that desire causes suffering and only the cessation of desire can alleviate suffering. Here, desire is not only acceptable, it is linked to both the grace of God and the heart of loving/worshiping God.

For some people, especially those steeped in fundamentalist or otherwise dualistic ways of approaching spirituality, the idea of taking delight in God may seem counterintuitive or simply off the map. And yet, here the Bible itself invites us into this way of relating to the Divine: not out of fear, or merely the observance of custom or the fulfillment of duty, but to exult in God, to enjoy and cherish the experience of relating to God, and to find in such a relationship an experience of delight. This paves the way for the fulfillment of desire — but not just any casual desire, rather, we are promised the gift of our heart’s desire: the desire or desires that matter most and are dearest to our heart (and not just our physical heart, but the heart of our soul).

When I speak about this verse, I like to say “We are not promised a new BMW. We are promised something far more valuable and meaningful — we are promised gifts that emerge from the center of our being” (not that there’s anything wrong with a new car! It’s just a very small desire when compared to what the heart longs for).

Finally, since we are reflecting on how positive images of desire can be found in the Bible, we need to acknowledge the Biblical text that has been loved and cherished by mystics throughout the centuries: the Song of Songs.

Also known as the Song of Solomon or the Canticle of Canticles, the Song of Songs is the great love poem at the heart of scripture. Just accepted at face value, it is a literary masterpiece: an exquisite and beautiful celebration of both desire and fulfillment, expressed through the mutual longing of a bride and groom. But over the centuries it has been read metaphorically or allegorically as an expression of the love flowing between God and Israel, or between Christ and the Church, or between the Holy Spirit and the individual believer. When we desire God, we are comparable to the achingly beautiful longing that two young lovers are capable of experiencing for one another. This is truly a beautiful and spiritually luminous desire: and so it forces us to reconsider any notion that desire is bad or suspect. The longing that two newlyweds hold for each other can be painful and can sting, but what a joyful longing it is — and likewise, what joy is there when a mere mortal longs for, desires, yearns for the love that creates and sustains all life, the love that flows at the very heart of all things.

In her book Pillars of Flame, Anglican solitary Maggie Ross suggests that there are three essential questions that can support the process of discernment, whether for personal or professional reasons. Those three essential questions for discernment are:

Where do I hurt?

What do I really want?

What price am I willing to pay for it?

Spiritual desire shows up in the second of these three questions. Like the desire of the heart, this question for what we really want invites us to a deeper place than the superficial desires that are often the result of casual whims (or consumer trends in society at large). We may want a nicer house or a faster car or a lovely vacation in an exotic setting, but are these things what we “really” want? Probably not, for what we really want is the desires of our hearts, the desires that emerge from the deepest places within us.

Perhaps when spiritual teachers like the Buddha, or the author of the Letter of James, criticize the very notion of desire, it is our superficial desires they are denouncing. Superficial desires really do seem to lead us into suffering, at least some of the time. Granted, deeper desires can sting as well, but perhaps they are always embedded in a sense of trust in the Divine. C. S. Lewis wrote beautifully about what he described as sehnsucht, from the German word for longing. In his afterword to The Pilgrim’s Regress, Lewis writes:

The experience is one of intense longing… though the sense of want is acute and even painful, yet the mere wanting is felt to be somehow a delight. Other desires are felt as pleasures only if satisfaction is expected in the near future: hunger is pleasant only while we know (or believe) that we are soon going to eat. But this desire, even when there is no hope of possible satisfaction, continues to be prized, and even to be preferred to anything else in the world, by those who have once felt it. This hunger is better than any other fullness; this poverty better than all other wealth.

The desire that is itself a kind of fulfillment? Where the sting of this longing is to be preferred over a life where such longing is never experienced? This, it seems to me, brings us closer to the heart of the ultimate mystery than any binary understanding of desire could ever do.

Such mystical desire functions not as a source of suffering (even if it seems to sting), but rather as an invitation into an humble life, shaped and formed by the fruits of the spirit: love, joy, peace, goodness, kindness, and so forth. The desire for the fruit of the Spirit is very close to the infinite/ultimate desire: the desire for union with God. To immerse ourselves in this desire is to find a longing that can never be fulfilled, and yet that will satisfy us more than any experience on earth might ever hope to do. May we all find that desire in our hearts, and cultivate it so that it may grow and shape our entire lives in response to limitless, boundless love.