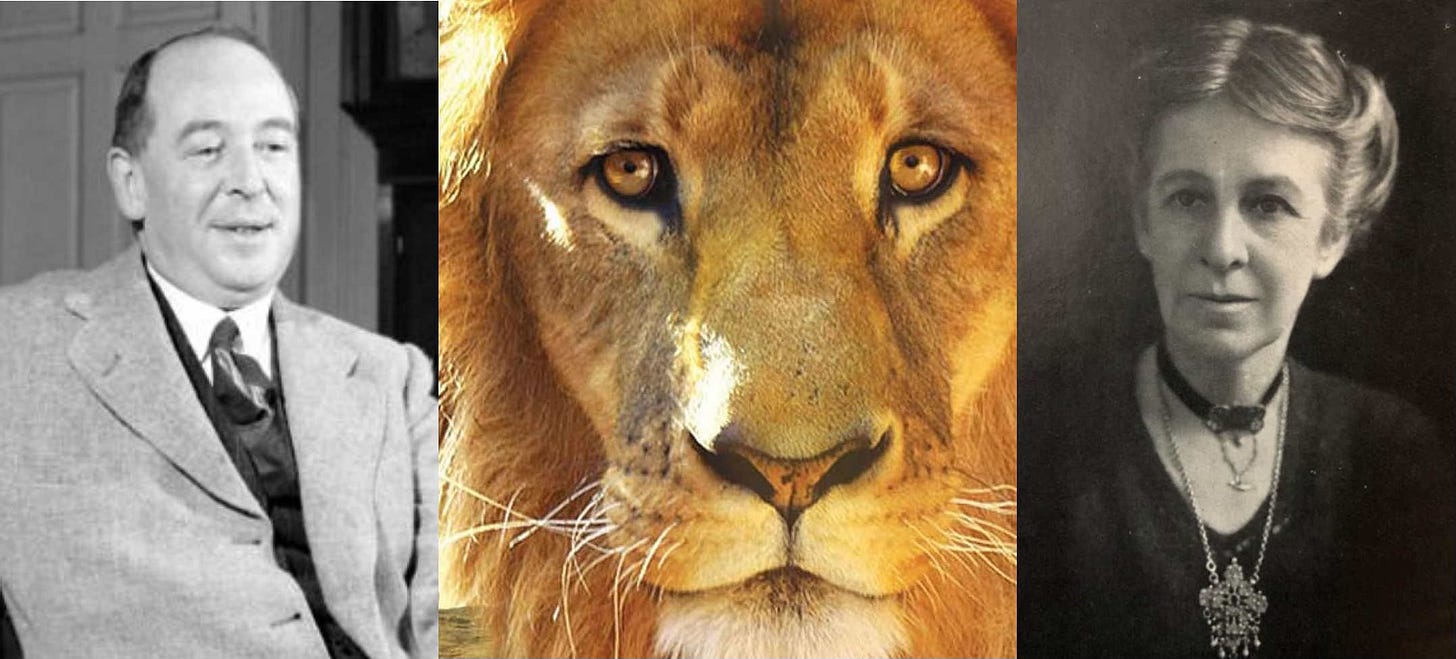

The Lion, the Mystic and the Professor

Did Evelyn Underhill inspire C.S. Lewis to write the story of Aslan?

On November 6, 1950, the American edition of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was published (the British edition had been published three weeks earlier). So for us Yanks, today marks the 75th anniversary of the first Narnia book.

To celebrate this date, I’d like to share with you my theory for how C. S. Lewis, the author of the Narnia books, may have been inspired to create the story of Aslan, the noble lion, who is the central character and indeed the heart and soul of the Narnia books.

My story begins with an interesting letter that was written in January 1941 (more than nine years before the first Narnia book was published) to Lewis, from the noted English author and scholar of Christian mysticism, Evelyn Underhill.

Underhill, who lived from 1875 to 1941, was the leading English authority on mystical spirituality in her day. Indeed, her book Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Spiritual Consciousness, published in 1911, is widely regarded as a classic introduction to that subject. She and Lewis corresponded several times before her death in June 1941. He was a generation younger than her, and it is apparent from their letters that he admired her and maybe even was a “fan.”

Several of Underhill’s letters to Lewis are preserved in The Letters of Evelyn Underhill, published shortly after her death (that book is now out of print, but fortunately a new edition of the letters of Evelyn Underhill has been published, titled The Making of a Mystic). These letters reveal that Lewis sent her at least two of his books, which she read and offered him discerning feedback. The correspondence is for the most part very warm. In 1938, Underhill praises Out of the Silent Planet, even though she admits to having a “decided prejudice” against science fiction. She lauds him for “the fact that you have turned ‘empty space’ into heaven!”

A couple of years later, though, when commenting on The Problem of Pain, Underhill seems less enthused — not only does she take issue with one aspect of the book, but she positively scolds Lewis about it.

He made a comment in the book about animals, which clearly angered Underhill. Apparently, in 1940 Lewis seemed to think that wildness was a bad thing; in other words, he seemed to think that animals were brought nearer to God by being domesticated by human beings. He wrote,

The tame animal is in the deepest sense the only natural animal… the beasts are to be understood only in their relation to man and through man to God.

For Evelyn Underhill, this is beyond just a stupid idea. To her, these were fighting words. And she did not shrink back from the challenge. I can only quote part of her reply, because of how long it is. But again, she scolds him. She writes:

This seems to me frankly an intolerable doctrine and a frightful exaggeration of what is involved in the primacy of man. Is the cow which we have turned into a milk machine or the hen we have turned into an egg machine really nearer the mind of God than its wild ancestor?

She is just getting warmed up. She alludes to William Blake as she continues to excoriate Lewis.

You surely can’t mean that… the robin redbreast in a cage doesn’t put heaven in a rage but is regarded as an excellent arrangement. Your own example of the good-man, good-wife, and good-dog in the good homestead is a bit smug and utilitarian, don’t you think, over against the wild beauty of God’s creative action in the jungle and the deep sea? And if we ever get a sideway glimpse of the animal-in-itself, the animal existing for God’s glory and pleasure and lit by His light (and what a lovely experience that is!), we don’t owe it to the Pekinese, the Persian Cat or the canary, but to some wild free creature living in completeness of adjustment to Nature a life that is utterly independent of man. And this, thank Heaven, is the situation of all but the handful of creatures we have enslaved.

She goes on to make a theologically nuanced argument about how humankind and the natural world may relate to the each other in the light of salvation. But she points out that humanity’s role in the “redemption and transfiguration” of the animal world will come about not through taming animals: “Rather by loving and reverencing the creatures enough to leave them free.”

Great writer that she is, she finishes her argument with a brilliant final point.

Perhaps what it all comes to is this, that I feel your concept of God would be improved by just a touch of wildness.

When Lewis replied, his letter (found in The Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis, Volume 2) is by turns defensive, charming, and conciliatory, without much insight into how Underhill’s perspective may have influenced his thinking. But I can’t help but engage in a delicious bit of speculation.

As I said, Underhill wrote the letter I’ve just quoted in January 1941, just months before she died. Some seven years would pass before Lewis wrote the first of his seven Narnia books, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, which he began writing in 1948. Today it is probably his best known book, no thanks to the continued popularity of the Narnia series as a whole. But it is in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe that readers were first introduced to Aslan, the noble Lion who symbolizes Christ himself. According to C. S. Lewis lore, the inspiration for Aslan came from a dream he had while writing the book, probably sometime in 1949. But I can’t help but wonder if the dream was the original impulse — or if, in fact, the inspiration had come years earlier.

In one of the most memorable passages in that book, the Pevensie children from England first learn about Aslan from a pair of talking Beavers:

“I tell you he is the King of the wood and the son of the great Emperor-beyond-the-Sea… Aslan is a lion— the Lion, the great Lion.”

“Ooh!” said Susan, “I’d thought he was a man. Is he— quite safe? I shall feel rather nervous about meeting a lion.”

“That you will, dearie, and no mistake,” said Mrs. Beaver; “if there’s anyone who can appear before Aslan without their knees knocking, they’re either braver than most or else just silly.”

“Then he isn’t safe?” said Lucy.

“Safe?” said Mr. Beaver; “don’t you hear what Mrs. Beaver tells you? Who said anything about safe? ‘Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.”

Then, almost at the very end of the story, when Aslan silently departs from Narnia in the midst of a great celebration, the conversation with the Beavers is recalled.

Mr. Beaver had warned them, “He’ll be coming and going ,” he had said. “One day you’ll see him and another you won’t. He doesn’t like being tied down— and of course he has other countries to attend to. It’s quite all right . He’ll often drop in. Only you mustn’t press him. He’s wild, you know. Not like a tame lion.”

Aslan is not safe — because he’s wild, you know. Not like a tame lion. I think Evelyn Underhill would have heartily approved, had she still been alive when this story was published.

In other words: Aslan finally represents C. S. Lewis depicting Christ (and, therefore, God) with “just a touch of wildness.”

I suppose we’ll never know for sure if Underhill’s passionate defense of wild animals directly inspired C. S. Lewis when he sat down a few years later to unleash Aslan in the Narnia stories. The answer to that question could only be found in the deep subconscious of the man himself, which he took to his grave in 1963. But I like to hope and think that maybe her words were an inspiration to him. At any rate, we are all the richer for the insight and imagination that went into the telling of the Narnia stories. And Evelyn Underhill’s letter would bring a smile to any animal lover’s face.

If you love Narnia, C. S. Lewis, and/or Evelyn Underhill, join me on a pilgrimage in search of the “Wisdom of the English Mystics” in England, May 27-June 2, 2026. For information or to sign up, click here.

Notes

Underhill’s 1-13-1941 letter to C. S. Lewis is found on pages 300-302 of The Letters of Evelyn Underhill and on pages 340-342 of The Making of a Mystic.

Lewis’s reply, dated 1-16-1941, is found on pages 459-460 of The Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis, Volume 2.

Read about the publication of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe here: “Harper Collins Children’s Books Celebrates 75 Years of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe”

This post is adapted from a talk I gave at a CS Lewis Symposium at Grace Episcopal Church in Gainesville, GA in 2017.