The Mystics of Middle-Earth

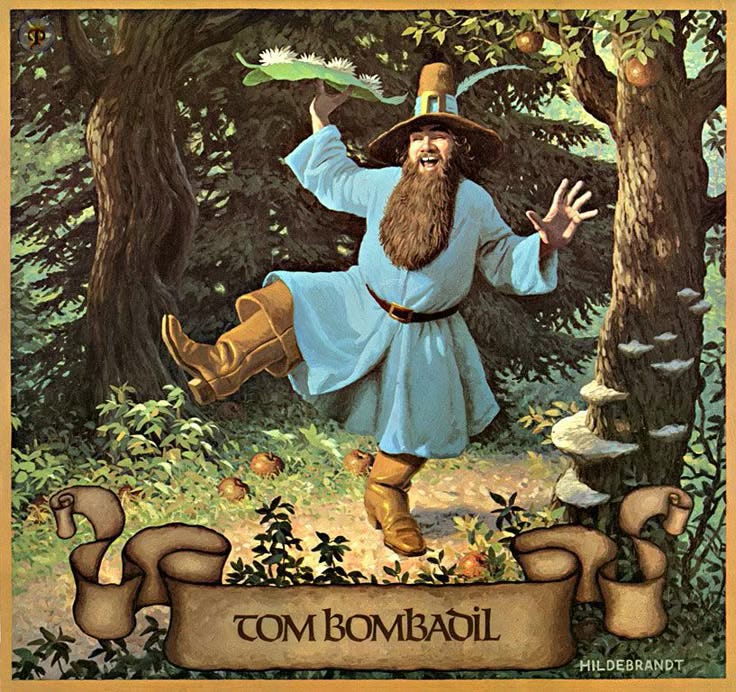

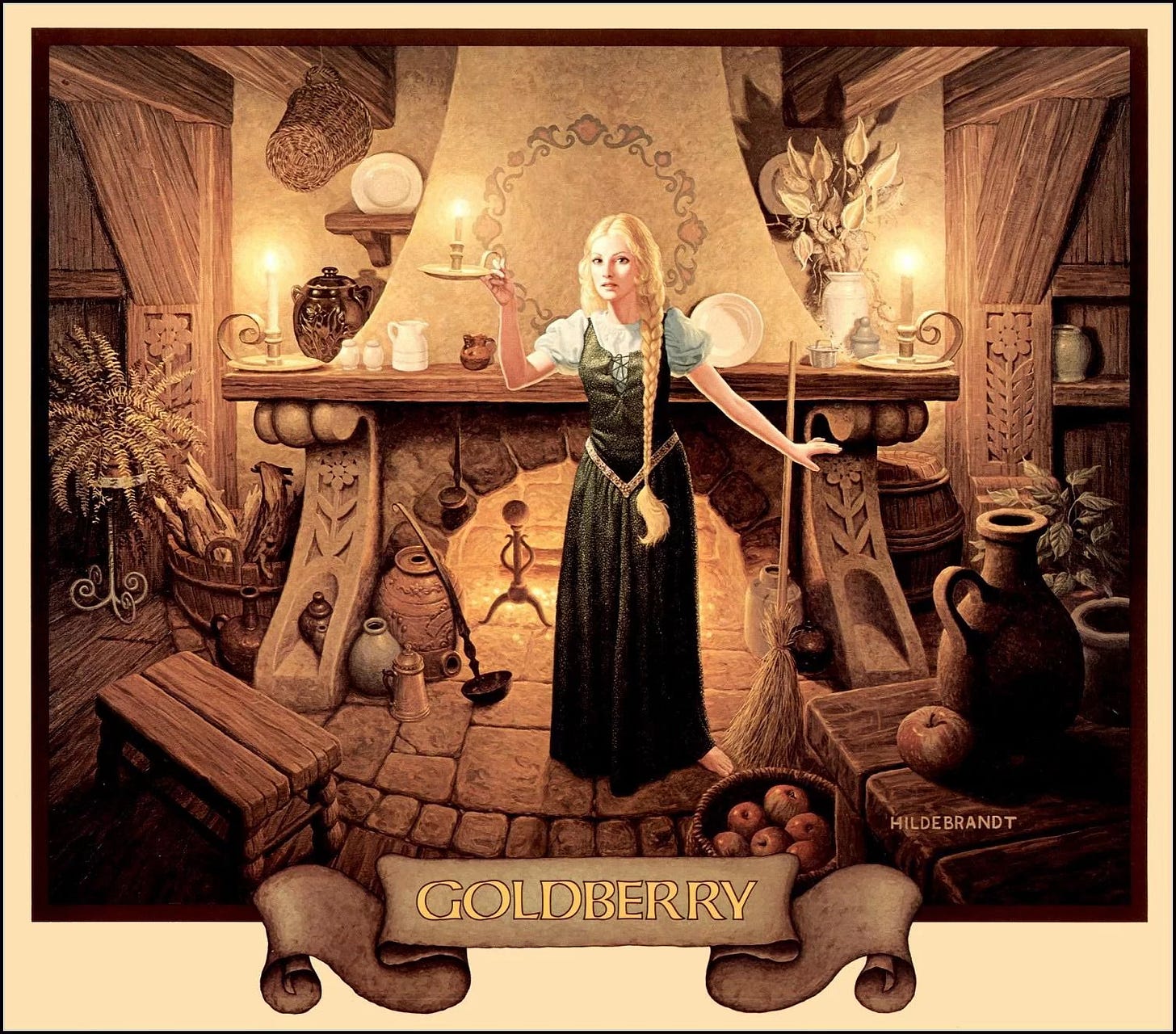

The Unnecessary Beauty of Tom Bombadil and Goldberry, the River's Daughter.

September 26 is a special day in the story of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. It is the day when Tom Bombadil rescued Merry and Pippin from Old Man Willow, and then invited the four hobbits (including Frodo and Sam) to spend two restful and beautiful nights in the home he shared with his beloved Goldberry.

If your knowledge of The Lord of the Rings is limited to the movies directed by Peter Jackson, you may have no idea what I am talking about here. And that is because the characters of Goldberry and Tom Bombadil were cut from the screenplay for the movie adaptation.

More’s the pity, for — as far as I’m concerned — Goldberry and Bombadil are two of the most important characters in the entire epic story of Frodo’s quest to destroy the one ring.

Not that I blame Peter Jackson and his co-writer, Fran Walsh. There is simply just too much detail, backstory, world-making, and mythology in Tolkien’s literary masterpiece to do the entire epic justice — even with 11 hours of time to tell the story in cinematic form. So Jackson and Walsh had to narrow the focus of the story to include just the characters, subplots and details that actually contributed to moving the main plot forward.

And as wonderful as the characters of Bombadil and Goldberry are — and as lovely as the episode in which the hobbits visit them is — the entire story could be excised from the main narrative without hurting the flow of the (main) story at all. So… goodbye Tom and Goldberry, beautiful characters: but completely unnecessary.

I contend that the story of Tom Bombadil and Goldberry is, by itself, reason enough to read the books, in addition to (or instead of) enjoying the film adaptation. Of course, the books deserve to be read for many reasons: Tolkien’s lyrical and limpid writing, his liberal use of poetry (often quite playful), the elegaic, mythical tone of his voice (Tolkien was steeped in Celtic and Norse mythology, and wrote The Lord of the Rings to echo those ancient mythopoetic traditions) and the sheer breathtaking beauty of this amazing world that he created, even as it is presented with the horrors of war and oppression on full display.

More than one readers’ poll conducted around the turn of the century selected The Lord of the Rings as the greatest novel of the twentieth century — and while fans of James Joyce and Marcel Proust might take umbrage at such a claim, no one can seriously argue that this deeply mythic, epic tale by a fussy and reclusive Oxford scholar isn’t one of the greatest literary achievements of the last 100 years.

The book is not perfect by any stretch — it reflects the blind spots of both its author and the culture which produced it, meaning that readers today can easily conclude that The Lord of the Rings suffers from a lack of meaningful and important female characters and the glorification of patriarchal masculinity. Some readers might bristle at the book’s not-so-subtle Catholic worldview (even, though, ironically, it became a favorite of hippies and neopagans, not to mention the science fiction/fantasy community).

But there is no masterpiece of human literature that isn’t somehow compromised by the limitations or blindspots of its author, so I for one would rather read a brilliant book and frankly acknowledge its problems, then to refuse to read it because I object to the fact that the author conforms to the sensibility and prejudices of its time.

But I digress. Let’s just say, if you haven’t read The Lord of the Rings, do so. It’s worth it, warts and all. Now, let’s get back to the topic at hand: Tom Bombadil and Goldberry, the River’s Daughter.

Who are these characters? They are both mysterious, both speak in riddles, and both leave the reader with more questions than answers.

Consider this revealing (or not-so-revealing) bit of dialogue:

‘Fair lady!’ said Frodo again after a while. ‘Tell me, if my asking does not seem foolish, who is Tom Bombadil?’

‘He is,’ said Goldberry, staying her swift movements and smiling.

Frodo looked at her questioningly. ‘He is, as you have seen him,’ she said in answer to his look. ‘He is the Master of wood, water, and hill.’

‘Then all this strange land belongs to him?’

‘No indeed!’ she answered, and her smile faded. ‘That would indeed be a burden,’ she added in a low voice, as if to herself. ‘The trees and the grasses and all things growing or living in the land belong each to themselves. Tom Bombadil is the Master. No one has ever caught old Tom walking in the forest, wading in the water, leaping on the hill-tops under light and shadow. He has no fear. Tom Bombadil is master.’ (Page 124)

So Tom is a “master” and he just “is,” but not much else is revealed about the strange character, who is bigger than a hobbit and smaller than a human.

Likewise, Tolkien only provides the most oblique of information about Goldberry. More than once Tom speaks lovingly of her as “the River’s Daughter,” but little else is said, although Tolkien can’t resist depicting her as embodying the romanticism of a pre-Raphaelite painting:

There on the hill-brow she stood beckoning to them: her hair was flying loose, and as it caught the sun it shone and shimmered. A light like the glint of water on dewy grass flashed from under her feet as she danced. (p. 135)

Tom Bombadil’s appearance in the story functions like a triptych, or a three-part symphony where the first and third movements echo each other: in the first “movement,” Bombadil rescues two of the four hobbits from a frightening encounter with Old Man Willow, an angry old tree that captures Merry and Pippin during their “trespassing” through his forest. After this near-disaster, Tom insists the four hobbits come to stay with him and Goldberry, which forms the second “movement” — but when he sends them on their way two days later, he has to rescue them again, this time from an evil Barrow-Wight, a hostile spirit that the hobbits encounter when caught in a fog near an ancient burial sight. That serves as the third and final movement of Tom’s “symphony.”

Thus, the hobbits’ encounter with Tom begins and ends with him rescuing them from a dangerous crisis. If Tom can protect our diminutive heroes from threats both natural and supernatural, clearly he is a figure of some power in himself. This is especially brought home by the way he interacts with the malevolent ring that Frodo has been tasked with carrying to Rivendell — a ring of untold evil but curious magic, including the ability to make whoever is wearing it vanish from sight.

‘Show me the precious Ring!’ he said suddenly in the midst of the story: and Frodo, to his own astonishment, drew out the chain from his pocket, and unfastening the Ring handed it at once to Tom.

It seemed to grow larger as it lay for a moment on his big brown-skinned hand. Then suddenly he put it to his eye and laughed. For a second the hobbits had a vision, both comical and alarming, of his bright blue eye gleaming through a circle of gold. Then Tom put the Ring round the end of his little finger and held it up to the candlelight. For a moment the hobbits noticed nothing strange about this. Then they gasped. There was no sign of Tom disappearing!

Tom laughed again, and then he spun the Ring in the air – and it vanished with a flash. Frodo gave a cry – and Tom leaned forward and handed it back to him with a smile. (p. 132-33)

As Gandalf would later explain, the ring had no power over Tom Bombadil — although Bombadil himself was not mighty enough to destroy or neutralize the ring, clearly he was no ordinary mortal in his capacity to withstand the ring’s influence.

Who, then, is this mysterious Tom Bombadil?

Critics and fans of The Lord of the Rings have no real consensus about this enigmatic character. He does not conform to any of the four main types of good beings in the story: humans, hobbits, elves and dwarves. Nor is he a wizard like Gandalf, but is someone Gandalf himself considers a peer (which may help to explain why Goldberry regards him as a “master” of the forest). And while Tolkien almost never gives his female characters much to do, I think it’s essential to consider who Tom is by viewing him alongside the River’s daughter, to whom he is clearly devoted and who seems to be is equal in love and hospitality, if not in power.

I find that there are two ways I think about Goldberry and Tom. The first is more “pagan” and the other more “contemplative” — but I think these two approaches complement each other, and so I hope you will find them thought-provoking as you explore your own perspective on these enigmatic characters.

In a pagan sense, I regard Goldberry and Tom Bombadil as archetypes of the deities of the land: representing the god and goddess of ancient lore and of indigenous mythologies from around the world. This theory might seem flawed, since Tom and Goldberry do not exhibit any kind of ultimate power. But often the indigenous gods and goddesses of primal cultures — the genius loci or guardian “spirits of the place” — only have a relative power, not cosmic or ultimate like the supreme being of monotheistic spiritualities, but figures that manifest the energies and blessings of the place where they dwell. It is clear that Tom has no interest in travelling far afield from his home in the old forest along the Withywindle River, a tributary to the larger Brandywine River; Goldberry, the Withywindle’s daughter, seems even more firmly rooted in her place, not venturing far from the lovely home she shares with Tom, a place of sumptuous hospitality, comfortable lodging, mouthwatering food, and endless song and story.

Mythical goddesses and gods can be powerful magical beings, but their power often is limited and relative: no pagan deity can protect their land from the ravages of human over-consumption, for example (although the malevolence of Old Man Willow makes sense when we consider that the forest does not like the gluttonous humans that occasionally venture into it).

Some readers might not like to think of these characters in a pagan sense, or might (like me) feel that this approach does not begin to exhaust the mystery of Goldberry and Tom Bombadil. So, I’d like to suggest another (or a corollary) way to meet our forest dwellers: that Tom Bombadil and Goldberry are the archetypal mystics of Middle-Earth.

This means that Goldberry and Bombadil are the ultimate nondualists of middle earth.

If the forces arrayed around the leadership of Aragorn and Gandalf are the “good guys” and the misshapen orcs and demons that obey Sauron and Saruman are the “bad guys,” it’s easy to see the Catholic cosmology at work in The Lord of the Rings — but it’s very much a temporal Catholic cosmology, a kind of dualistic study of the eternal conflict between angels and demons. The great heroes of this story are like great saints: they embody wisdom, courage, compassion, and sacrifice, but they remain completely defined by the fight they find themselves in the midst of. Eowyn, for example, is a heroine, but her heroism is completely shaped by the conflict she is thrust into by the events of her age.

Meanwhile, Tom Bombadil and Goldberry live an eremitical (hermit-like) life, deep in the forest, where they embody classic spiritual virtues such as kindness, generosity and hospitality, woven together with a rich appreciation of the power and beauty of nature and a no-nonsense understanding that forces of harm have no final power over them (or their guests). They live a simple life but one marked by beauty, from the beauty of nature to the lyrical singing and dancing they continually embody, and of course the ethereal feminine beauty of Goldberry herself.

Contemplative spirituality — mysticism — is the spirituality of beauty. Just as systematic or “dogmatic” theology is the stories we tell ourselves to discern divine truth; and moral or ethical theology is the expression of sacred goodness; so the mystical or contemplative way is the path of apprehending and celebrating heavenly (and earthly) beauty, beauty that arises from the heart of the holy mystery. In The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf, Galadriel and Elrond represent the wisdom of truth; Aragorn, Arwen Evenstar and Gimli represent the courage of goodness, and so Tom Bombadil and Goldberry are icons of mystical beauty. Our mysterious mystics live on the margins of the world of Middle-Earth, sharing their hospitality and joy and maintaining a simple life in harmony with nature and of service to those who come to be their guests — just like contemplatives have done over the centuries in the monasteries and other sacred centers around the world.

After they had eaten, Goldberry sang many songs for them, songs that began merrily in the hills and fell softly down into silence; and in the silences they saw in their minds pools and waters wider than any they had known, and looking into them they saw the sky below them and the stars like jewels in the depths. (p. 132)

Like all mystics, Goldberry and Bombadil recognize that even their words, poems and songs exist only against the backdrop of deep silence. Tom’s songs and poems are especially nonsensical, although Tolkien suggests that they might represent “a strange language unknown to the hobbits, an ancient language whose words were mainly those of wonder and delight.” (p. 146)

But even Tom’s wonder and delight shade off into silence, profound silence, where the hobbits discern the bottomless waters of their subconscious minds — or perhaps of the collective unconsciousness of all sentient beings; but these are celestial waters, where even the sky and the stars are “below them” — reflected in the waters of the silence, of course, but also occupying a place of great depth, deeper even than the silence itself.

Dreams abound in the house of Tom Bombadil and Goldberry: the first night they sleep there, all of the hobbits save for Sam experience vivid dreams. But in the morning of the second night, just before leaving this haven in the forest, Frodo has the most mysterious inner encounter of all:

Either in his dreams or out of them, he could not tell which, Frodo heard a sweet singing running in his mind: a song that seemed to come like a pale light behind a grey rain-curtain, and growing stronger to turn the veil all to glass and silver, until at last it was rolled back, and a far green country opened before him under a swift sunrise. (p. 135)

If you flip forward to the very end of this lengthy epic, after Frodo has sailed with the other ring bearers from the Grey Havens (a heartbreakingly beautiful metaphor for death), Tolkien bids his hero farewell like this:

Then Frodo kissed Merry and Pippin, and last of all Sam, and went aboard; and the sails were drawn up, and the wind blew, and slowly the ship slipped away down the long grey firth; and the light of the glass of Galadriel that Frodo bore glimmered and was lost. And the ship went out into the High Sea and passed on into the West, until at last on a night of rain Frodo smelled a sweet fragrance on the air and heard the sound of singing that came over the water. And then it seemed to him that as in his dream in the house of Bombadil, the grey rain-curtain turned all to silver glass and was rolled back, and he beheld white shores and beyond them a far green country under a swift sunrise. (P. 1030)

Hmmm. If sleeping in a house where you dream clearly of heaven doesn’t mark that house as the house of a mystic, then I don’t know what would do the trick. But whether we want to label Tom (or Goldberry) as mystics is really beside the point. As Kenneth Leech once said to me, what matters is not being called a mystic, it’s living a mystical life. And Goldberry and Tom Bombadil certainly seem to be doing just that.

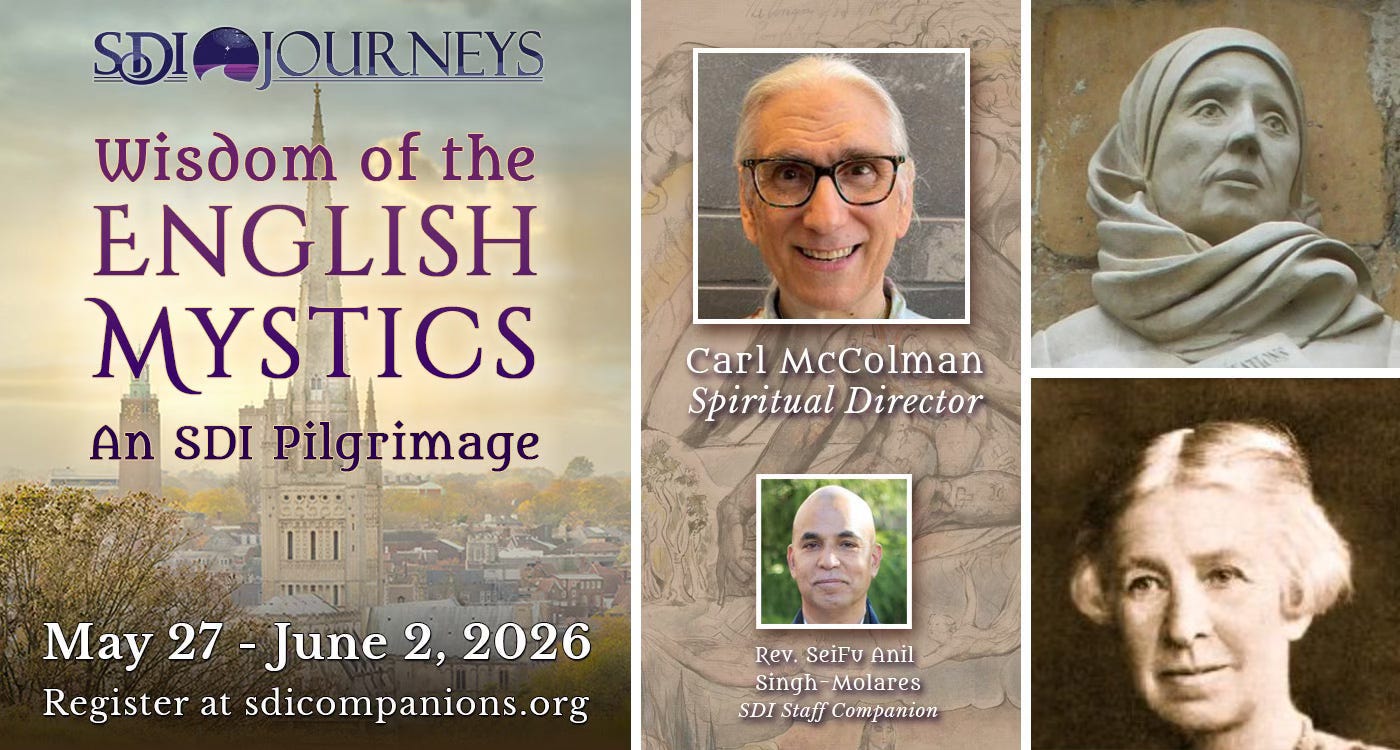

If you love Evelyn Underhill (and Julian of Norwich, William Blake, and other English mystics), join me on a pilgrimage in search of the “Wisdom of the English Mystics” in England, May 27-June 2, 2026. For information or to sign up, click here.

Quotation Sources: all page numbers correspond to the “One Volume” Kindle edition of The Lord of the Rings.